* Life * Research * Experiments * Media < back

How Eduard Rüppell researched and gain his knowledge

Eduard Rüppell traveled as a researcher to foreign countries and unknown areas. These journeys were very expensive, and Rüppell had to prepare properly: he required the right equipment and astronomical devices to be able to determine his location and his routes.

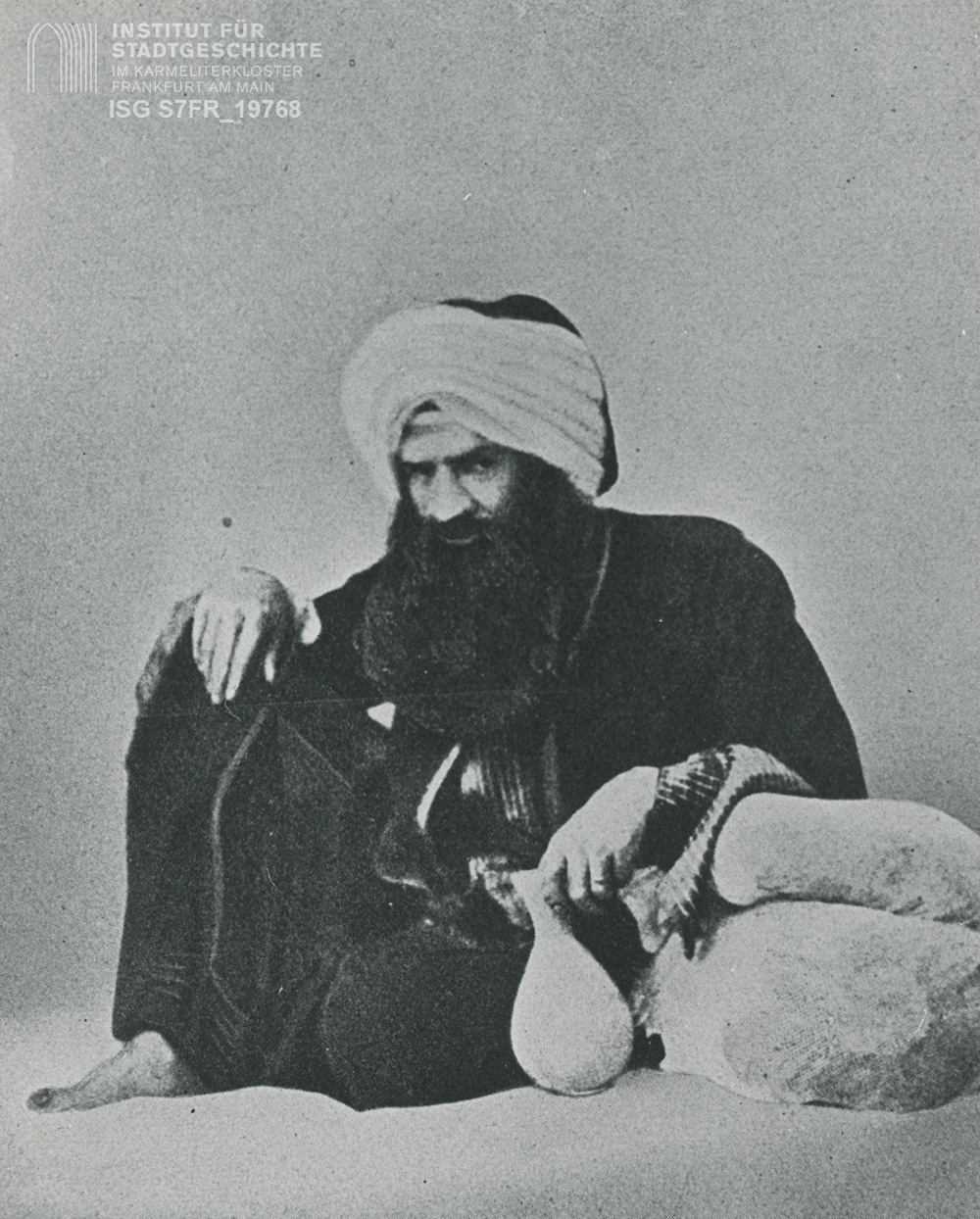

He also had to know about the weather, landscape and geography and be able to communicate verbally. Within the space of 30 years, he undertook four large expeditions to East Africa, Nubia, Egypt, Ethiopia (then called Abyssinia) and to the Red Sea. He had to survive many adventures, struggling with pirates, warring tribes, illnesses and heat, hunger and thirst. But none of this seemed to bother him much, and did not prevent him from exploring the foreign surroundings with great curiosity.

Rüppell focused mainly on previously unexplored mammals, birds, reptiles, crabs - and his favorites: fish species - observing their appearance and habitats. In 1842, he was the first to describe the naked mole-rat, which had been caught in an Ethiopian city. He gave it the scientific name Heterocephalusglaber (which roughly means ‘smooth, (bald) other-headed’ in German).

Rüppell had some of the observed animals killed, preserved and sent by ship to Frankfurt. This even included a hippopotamus, a giraffe, and a manatee he had received from pirates. The people at home in Frankfurt were able to marvel at an immense number of exotic animals they had never seen before. But that was not the main reason why Rüppell brought all these animals back to Frankfurt. Here he wanted to study the animals more closely, and continue his research with the help of his notes.

He categorized the species according to certain characteristics and created large collections, which he was able to enlarge by cleverly trading some of his objects. These collections, which he donated to the Senckenberg Research Society, were also of great interest to other scientists.

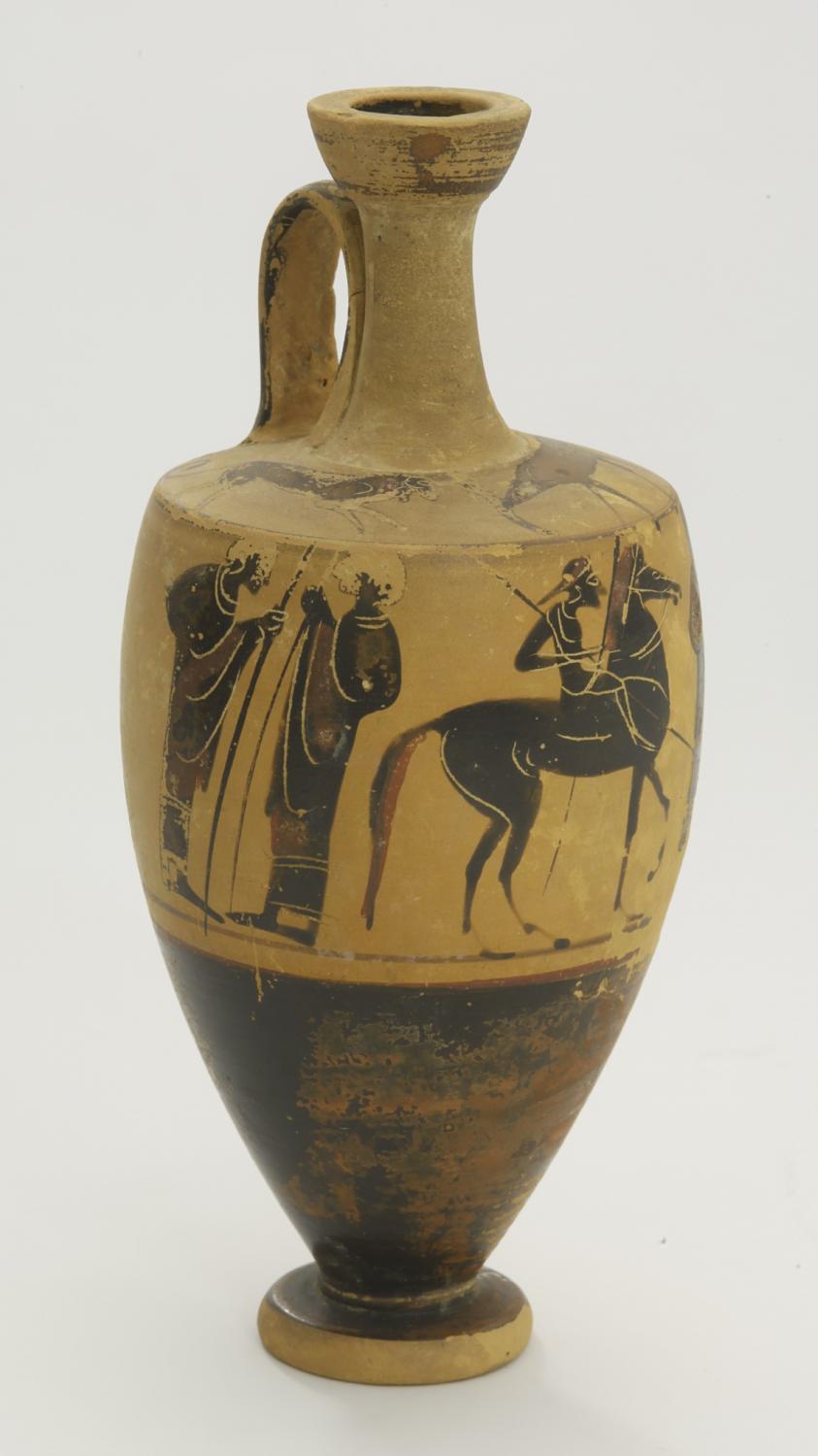

Since Eduard Rüppell was very inquisitive, he brought not only animals from his travels, but also archaeological finds, old writings and coins. When he grew older and could no longer undertake strenuous trips for health reasons, he pursued his research with these objects, especially with coins.

How Eduard Rüppell researched and gaind his knowledge

Travel was something particularly special at the time of Eduard Rüppell's childhood. But Edward's father traveled frequently, and often took one of his children with him. At the age of seven, Eduard journeyed to Salzburg and Berchtesgaden. There he visited the salt mines and was given a small collection of minerals, which he supplemented with things he had collected himself. He traveled to Hamburg at the age of eleven with his father, and was very impressed by the port and the many ships.

On instructions from his father, Eduard wrote letters to his brothers and sisters at home, sharing his experiences. In this way he learned to observe and describe things exactly. At that time he also began enthusiastically reading travel descriptions. This aroused his passion for traveling and collecting, writing and documenting.

Rüppell’s first major trip was to Egypt. He was originally only supposed to accompany a consignment for a trading house he worked for at the time, but it turned into a ten-month stay. During this time he met two research travelers, the Swiss Johann Ludwig Burkhardt and the Englishman Henry Salt. Rüppell was so enthusiastic that he gave up his commercial profession and decided to live as a traveler, explorer and researcher.

How Eduard Rüppell documented his findings

During his travels, Eduard Rüppell described and drew all living things that interested him. In addition to this documentation, he simply took original objects with him.

He had animals and plants preserved, and collected special stones, coins, archaeological excavations, works of art and old manuscripts. This led to whole shiploads of the most diverse collections arriving in Frankfurt. He quickly passed on his treasures, donating them to various museums and the Senckenberg Natural Science Society, later the Senckenberg Museum, which was founded in 1821.

Rüppell wanted the objects to be publicly accessible to a broader audience. He himself could of course visit and study his assembled collections at any time, and lived very close to them, directly opposite the Senckenberg Museum at the Eschenheim Tower.

He wrote several books based on his biological research results and findings. But Rüppell was also active in a variety of scientific fields, writing a book on coinage in 1855.

How Rüppell's findings were advanced and the importance of his research today

Because Eduard Rüppell gave his collections to museums, they have been preserved to the present day, and can be viewed by visitors and used by scientists for research purposes. His collections of around 4000 mammals, fish and birds became the basis of the Senckenberg Museum.

Because Eduard Rüppell gave his collections to museums, they have been preserved to the present day, and can be viewed by visitors and used by scientists for research purposes. His collections of around 4000 mammals, fish and birds became the basis of the Senckenberg Museum.

He passed on further collections to Frankfurt’s city library, from which the Historical Museum later received its coin collection - Rüppell had bought a total of 10,000 coins in Egypt; Egyptian figures and other ancient objects were donated to the Liebieghaus.

For a long time, nobody was interested in how Eduard Rüppell acquired all of these items. Only in the past few years have questions about the origin of objects Rüppell and many others brought from Africa to Europe been asked: Were they simply taken, meaning stolen? Was far too little money was paid for them? Did the owners even agree to the trade? Shouldn’t many objects be returned? And so on. These are difficult issues to deal with, since many still think, just as 150 years ago, that objects of art from other cultures are particularly well looked after and protected in Europe, and can be particularly well researched here.

But Eduard Rüppell was not simply a collector: he was above all a research scientist, and many of his fundamental scientific findings are still valid today. The naked mole-rats he investigated are particularly interesting for modern medical research.

Naked mole-rats are five to fifteen centimeters long, weigh from 30 to 50 grams and have few very fine hairs, which is why they appear to be naked - hence their name. Naked mole-rats have unusual characteristics and can live to be 20-30 years old, which is very old for rodents. They hardly feel pain, don't get cancer, and can also live without oxygen for up to 18 minutes.

Doctors are researching which substances in the animal's body are responsible for these properties, and whether the results can be transferred to humans - for example, in the treatment of pain or in preventing or curing cancer. For instance, when a person has a heart attack or stroke, the cells surrounding the closed blood vessel immediately die, since they are no longer receiving oxygen.

Researchers are looking for ways to prevent cells from dying and the resulting diseases, and can perhaps gain knowledge from the ability of the naked mole-rat to survive without oxygen for so long. In any case, many naked mole-rats now live in high-tech laboratories around the world.

* Life * Research * Experiments * Media < back