* Life * Research * Experiments * Media < back

How Paul Ehrlich researched and gained his knowledge

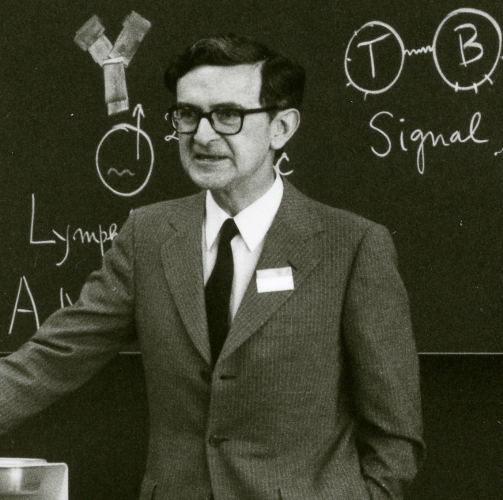

Paul Ehrlich researched and experimented mainly in the laboratory. During his student years he had already begun chemical staining (coloring) of tissue cells and examining them under the microscope, using the new tar dyes developed around 1850. Tar was actually a waste product of the coal industry, but in newly created chemical factories it was possible to produce bright colors from it.

At first the dyes were mainly used in the textile industry, but the medical profession soon recognized the use of color in their research. By using tar dyes, Paul Ehrlich was able as a student to discover a new type of cell in the connective tissue of frogs, which he named a mast cell; it plays an important role in the body's defense against pathogens. Ehrlich found out that cells can be distinguished not only by appearance but also by their chemical properties, made visible through the method of staining.

This finding was an important basis for the development of effective drugs. Ehrlich experimented often until late in the evening, leaving his work tables looking disorderly and discolored. His hard work earned him a reputation among professors, but also complaints from other researchers at the institute. Paul Ehrlich allegedly soiled his desk at the University of Strasbourg so badly that its surface had to be shaved off.

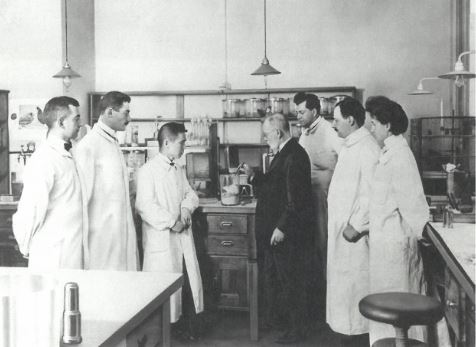

From his staining experiments at the Berlin Charité, Ehrlich also recognized that different types of blood cells exist. This made the doctors' work easier, since it had previously only been possible to identify many blood diseases after they were directly visible or palpable. Now doctors could detect diseases earlier by examining blood. Both during his studies and later as a young doctor at the Charité in Berlin, Paul Ehrlich was able to research independently and freely. He delegated many of his tasks to students or doctoral candidates, but did not give them the freedom that he himself had as a researcher.Ehrlich carefully planned their scientific work: at daily meetings and tours of the research departments, the colleagues discussed their results with Paul Ehrlich and received new work instructions from him.

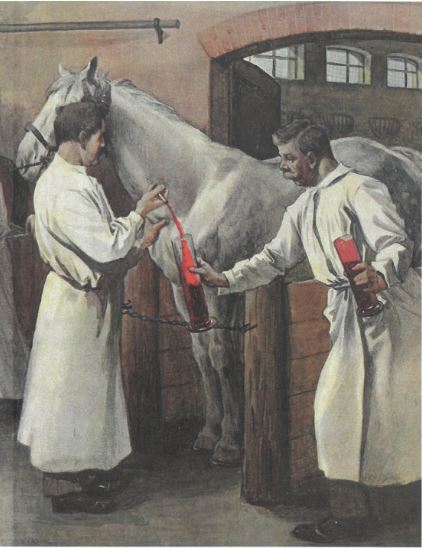

The Institute for Serum Research and Serum Testing in Berlin, led by Ehrlich, was originally housed in a former bakery and limited his work testing the serum against diphtheria, a dangerous throat disease. After moving from Berlin to Frankfurt in 1899, the institute was expanded and received new areas of responsibility. It was renamed "Institute for Experimental Therapy", and even had horse stables built. These were needed for testing because the diphtheria pathogen was injected into the horses; their body’s defense system then produced antibodies to the poison. The diphtheria serum was then obtained from the blood of the horses and used to vaccinate humans.

Paul Ehrlich shared his work with many colleagues during his career, including those from abroad. He also kept in touch with many important politicians and influential people, creating a network with many useful contacts that greatly helped him in his research. Thanks to the assistance of his friend Ludwig Darmstaedter and the donor Franziska Speyer, another particularly well-equipped institute, the Georg Speyer Haus, was built and inaugurated in 1906. As its director, Paul Ehrlich had even better conditions to continue his "experimental medicine" and research into the healing of illnesses with chemical drugs, the so-called chemotherapy.

How Paul Ehrlich came to his research subject

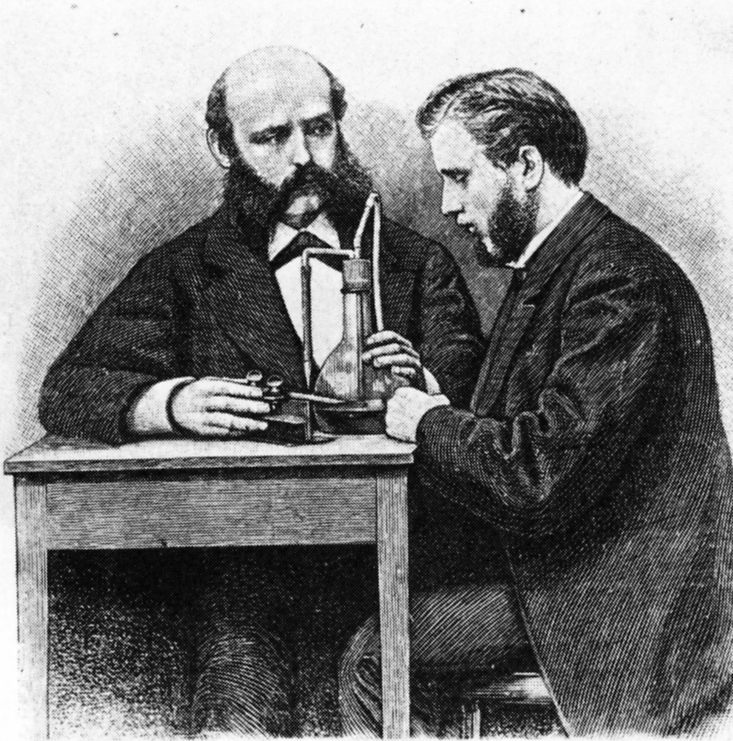

As a child, Paul Ehrlich visited his cousin Carl Weigert during the school holidays. Weigert Hworked at the University of Wroclaw, and as a pathologist studied the development of diseases. He was an expert in the field of chemistry and especially chemical staining (coloring). He was the first researcher to make bacteria visible using chemical dyes.

Perhaps it was the visits to his cousin that sparked Paul Ehrlich’s interest in chemistry, and triggered his career as a medical researcher. Likely influenced by Carl Weigert, Paul Ehrlich decided to study medicine after high school; other socially respected professions, such as lawyers, were also difficult for young adults from Jewish families to access. Ehrlich certainly showed an early interest in biology, dye chemistry and tissue staining during his studies. The medical courses and practical training he selected showed that he maintained this interest throughout his studies. In addition, he often accepted the offer of professors to use their facilities for private studies. His cousin was probably a great help to him, and his mentor when experimenting.

Paul Ehrlich's curiosity, his investigative spirit and also his lifelong love of crime novels probably contributed to his passionate interest in research.

How Paul Ehrlich documented his findings

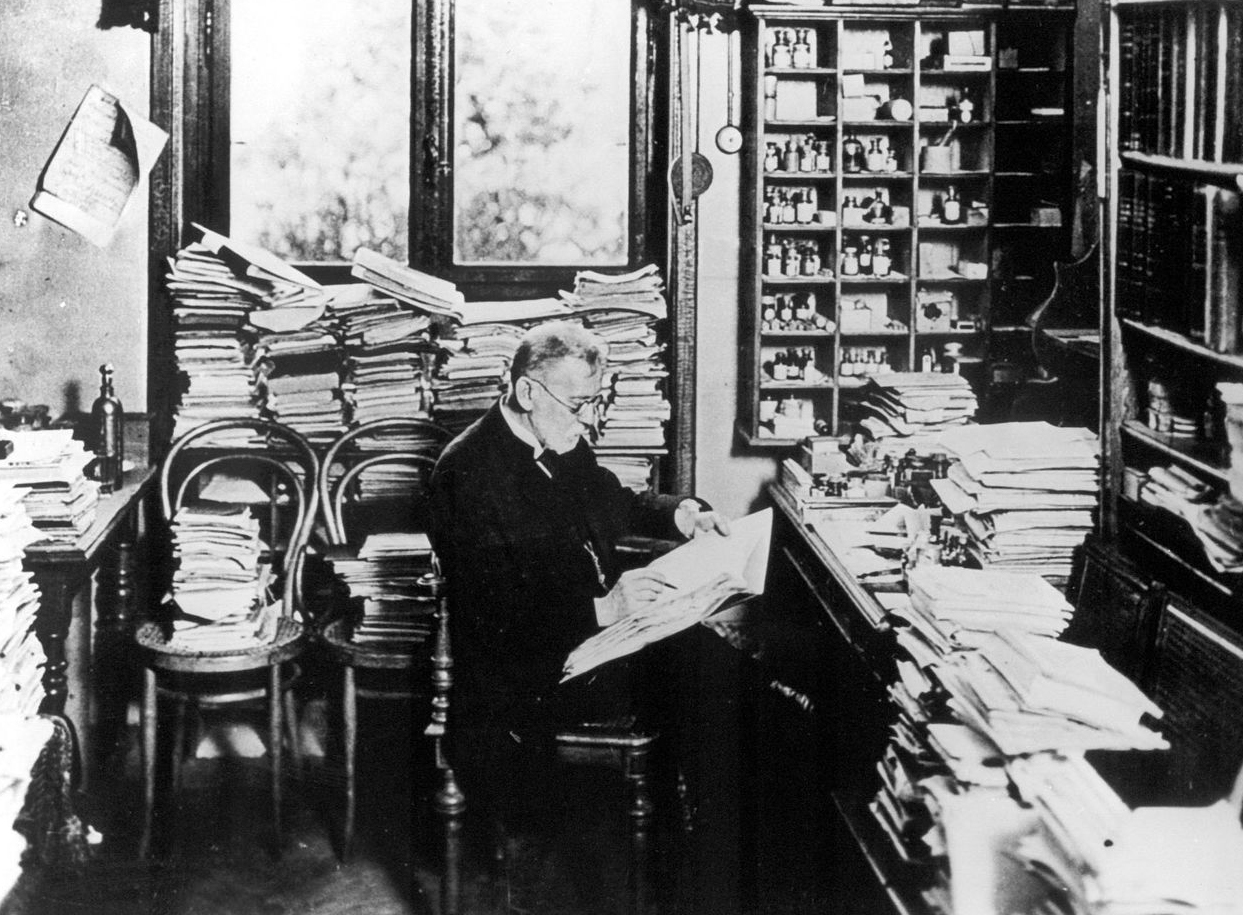

"Work a lot, publish little" was Paul Ehrlich's attitude to his work. Nevertheless, he made over 200 scientific publications during the course of his life. To write down his numerous ideas and thoughts, Paul Ehrlich used all possible document materials available to him. His secretary Martha Marquardt reported that he even wrote notes on floors, tablecloths, closet doors and shoe soles; the large quantity of test protocols were recorded in booklets.

"Work a lot, publish little" was Paul Ehrlich's attitude to his work. Nevertheless, he made over 200 scientific publications during the course of his life. To write down his numerous ideas and thoughts, Paul Ehrlich used all possible document materials available to him. His secretary Martha Marquardt reported that he even wrote notes on floors, tablecloths, closet doors and shoe soles; the large quantity of test protocols were recorded in booklets.

He explained his work in letters to his German or foreign colleagues. Sometimes he even enclosed whole copies of his research with the letters, and asked his colleagues to publish them. He also presented his results at scientific conferences and numerous lectures at home and abroad.

In 1914, on the occasion of his 60th birthday, a commemorative publication in honor of Paul Ehrlich was published by his teachers, staff and friends. His entire research work was presented in this commemorative publication.

How Paul Ehrlich's findings were advanced and the importance of his research today

Paul Ehrlich acquired a great deal of knowledge about chemical processes that take place in the human body. His experiments and theories are still the basis for modern medical research. Even if some methods are no longer in use, they were an important step in the development of numerous findings.

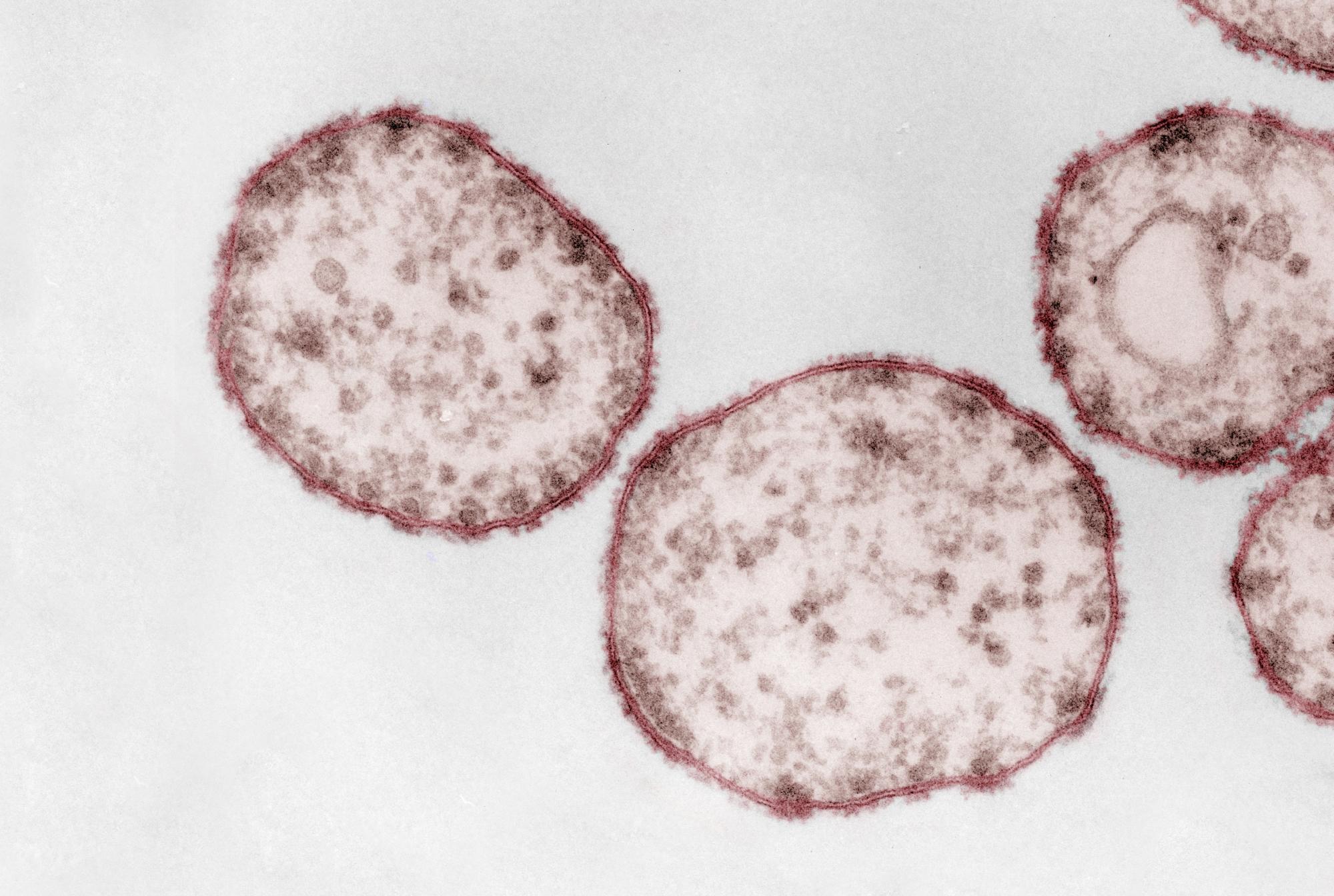

The dyeing method, for example, made things visible that were previously hidden. Colors with different properties (basic, acidic and neutral) made it possible to highlight chemical properties and pathological changes in cells or blood, and see them under the microscope. The microscopes used at that time are today no longer employed, and the staining method has become less common; modern, strong magnifying electron microscopes make cell staining unnecessary.

Paul Ehrlich was the first to comprehensively recognize the importance of the human immune system, with his so called side-chain theory. He described how it plays a central role in many diseases and is responsible for the defense against pathogenic bacteria and viruses in an organism. Ehrlich's theory assumed that there is a kind of chain on the sides of each cell within an organism. Pathogens can latch onto the chains of cells in the organism like "keys and locks", making the healthy cells unusable. In response to the “chaining” of the pathogen only a certain type of cell in the organism, called B-cells, are able to produce antibodies, meaning defenses against a disease.

The side-chain theory was later linked to the theory of scientist Niels Kaj Jerne and further advanced, but the assumption that harmful foreign bodies attack cells in the body by “chaining” to them is essentially still valid today. Based on this knowledge of how an organism works and diseases arise, Paul Ehrlich was also able to search for their cures.

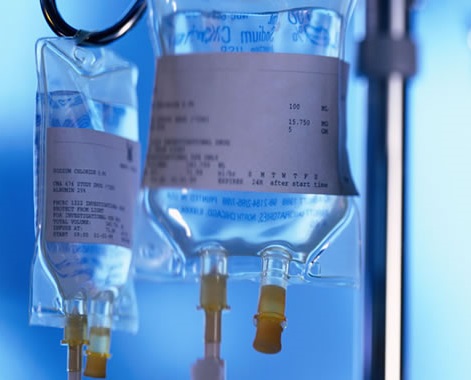

In collaboration with Farbwerke Hoechst, a chemical factory near Frankfurt, he launched in 1910 the drug Salvarsan. It consisted of a chemical agent that only “chained” itself to the pathogen of the infectious disease syphilis and “poisoned” it. Salvarsan marked the beginning of chemotherapy.

Many drugs that work along the same principle have followed to the present day, targeting the destruction of pathogens in the human body through the use of chemical agents. Today chemotherapy is used not only in the treatment of infections, but also in cancer.

* Life * Research * Experiments * Media < back