* Life * Research * Experiments * Media < back

What was special about Tilly Edinger's research?

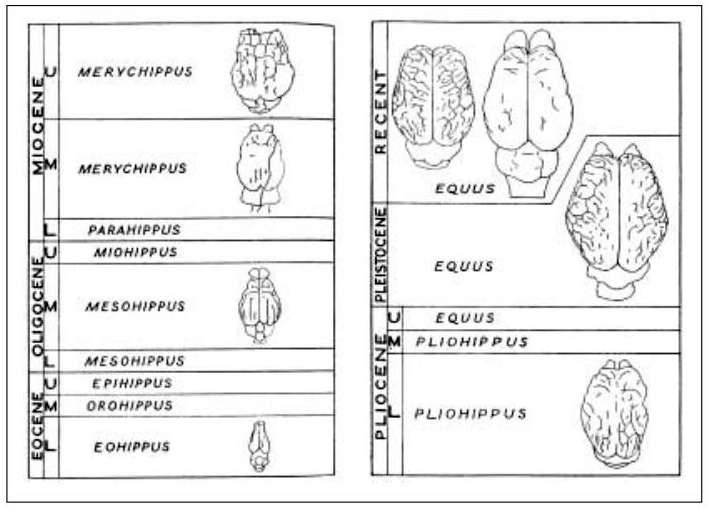

Tilly Edinger’s scientific field of work of was researching the brains of vertebrate animals. She examined fossils that were millions of years old, comparing different brain matter, from bats to dinosaurs, but also matter within an animal species. In this way she was able to understand how brains develop and change, as well as identifying similarities and differences with animals living today. Through these comparisons, Edinger drew conclusions about when certain skills, including those of long-extinct species, were developed.

Particularly important were her research works “About Nothosaurus”, an extinct fin lizard (1921), and "The Evolution of the Horse Brain", published in 1948 in the United States – where she, as a Jewish woman, was forced to flee from the German National Socialists.

Tilly Edinger developed her field, called paleo-neurology, into an independent area of science. Her research is considered an important contribution to a modern understanding of evolution, the theory of the development and mutation of living things. Tilly Edinger's findings still serve as a basis when today’s paleontologists study vertebrates from past geological ages.

The course of Tilly Edinger's life

Johanna Gabriele Ottilie Edinger, called Tilly, was born on 13 November 1897, in Frankfurt. Her mother Anna Edinger fought for women's rights and peace, as well as against poverty and exploitation. Several social institutions were created through the mother’s activity.

Tilly's father Ludwig Edinger was a neurologist and brain researcher. As one of the founders of the Frankfurt University, he worked there as a professor of neurology. Tilly, as well as her older brother and sister, grew up in an educated, dedicated and wealthy family.

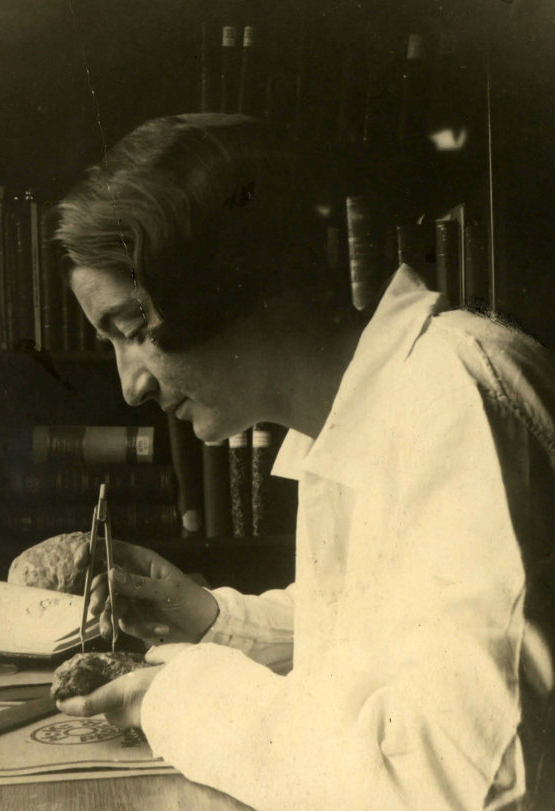

Tilly took private lessons until the age of twelve, then went to the Schiller School in Frankfurt - a girls' high school - where she graduated in 1916. She then studied Natural Sciences at the universities of Heidelberg, Frankfurt and Munich - beginning with geology, then zoology and paleontology. She wrote her doctoral thesis in 1921 on the fossil brain of Nothosaurus, a dinosaur that had lived more than 200 million years ago.

Tilly Edinger was the first woman in Germany to receive a doctorate in paleontology and remained the only one in this world of men for many years. She worked as a scientist at the Senckenberg Natural History Museum until 1938, where she researched vertebrate fossils. Tilly received no money for her work, remained unmarried and initially lived with her mother, who described Tilly Edinger's work as a "hobby".

She was also an assistant from 1931 to 1933 at the Neurological Institute of the Goethe University, which today is named Edinger Institute, after her father.

As an unmarried woman who was also hard-of-hearing, Tilly Edinger already had slim chances of finding a job as a science professor. And with the onset of National Socialist rule in 1933, all her remaining hopes were not only extinguished, but as a Jewish woman she was even in mortal danger. Tilly Edinger had long underestimated these dangers because her employer, the Senckenberg Natural Science Society, had allowed Jewish employees to continue working. Only after the November pogroms of 1938 was she barred from entering the museum. She managed to flee to London and earn some money there as a translator. Edinger had never had financial worries until that time, but now had to subsist with very little for a long period. After two years, she was allowed to travel to the USA.

Although she was able to continue work at Harvard University in her field of scientific expertise, she did not receive a position matching her skills and research achievements. Nevertheless, she stayed on at the University of Cambridge in the "Museum for Comparative Zoology", where she at least got the recognition of her colleagues, and was later elected president of the "American Society for Vertebrate Paleontology". Her book, “The Evolution of the Horse Brain”, was published in 1948, and is considered a milestone in modern evolutionary theory.

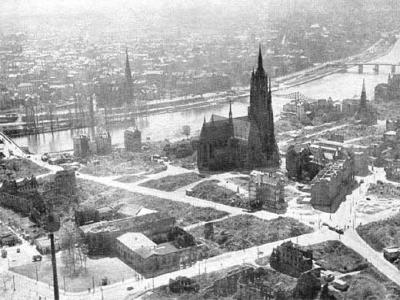

Tilly Edinger’s experiences in Germany had been terrible: she had been forced to flee, and some of her relatives were murdered there. Nevertheless, after the end of the Second World War she campaigned for German colleagues to be reinstated in the international scientific community, for example the "Society of Vertebrate Paleontology". She returned to Frankfurt for the first time in 1950, remarking "But that was so horrible, (...). And everything was so in ruins that I didn't know where I was. "

During her later visits, Tilly attempted to view Frankfurt not as a former local, but from the standpoint of a stranger - perhaps because she had had to fight so hard, into the 1960s, to retrieve at least part of her parents' property.

Tilly Edinger was run over by a car in 1967, on the street right in front of her workplace at the Harvard Museum, and died the next day, 27 May 1967. Her ashes were laid to rest in her parents' grave at Frankfurt's main cemetery.

* Life * Research * Experiments * Media < back